Great British Energy:

What should be created?

Steve Wardlaw, May 2024

Introduction

We are now in the general election cycle, where focus will be on votes and victory. That sometimes means that policy and implementation are (understandably) sidelined for these six weeks. Nevertheless the Labour Party has made ‘Set Up Great British Energy’ one if its six first steps.

Clearly, these first steps are very high-level summaries of action plans. I have talked BEFORE and will talk again (!) about what Great British Energy (GBE) is going to do. This piece talks about the essential first step. If you are setting up GBE, what structure are you going to use? What are the pros and cons of the various types of Government owned entities, and which type might suit GBE’s mission?

A side note first. One of my ongoing issues is that there is a lack of clarity about the purpose of GBE. For this article I am going to focus on the concept of developing an energy portfolio, and being a foundation investor or lender, so the more corporate parts of GBE’s remit. It is success in these areas that will drive the economic success of GBE, allowing a solid foundation to generate income that can replace Government spending on some green projects.

We are also looking at maintaining maximum flexibility in relation to the Government’s role. There are still discussions on the extent that the Government has operational control, or its role as a shareholder, lender or guarantor.

What are the options?

The National Audit Office in a dated but useful paper from 2015[1] listed the type of government companies, but the 4 main types are:

Companies incorporated by Royal Charter. A Royal Charter is used to incorporate a separate legal entity. A body incorporated by Royal Charter has all the powers of a natural person, including the power to sue and be sued in its own right, so very much like a recognisable company. These have no shares or members and are created by Royal Charter which sets out the terms of operation acting like a limited company’s memorandum and articles.

Companies created by legislation. These are also called statutory companies or corporations. They are created by bespoke legislation and have no shares or members. Again the legislation will define their powers and operation.

Private company limited by guarantee. The liability of the owners (members) on winding up the company is limited to the (usually nominal) amount stated in the company’s articles. It is commonly used for not-for-profit companies.

Private company limited by shares. The liability of its owners (the shareholders) is limited to the amount, if any, unpaid on the shares which cannot be publicly traded. Shares in government companies are typically owned by the Secretary of State and have a nominal value of £1 but this does not necessarily have to be the case.

In looking at these options, what criteria might the Government consider when making a selection.

Longevity. The advantage of legislative companies is that they need legislation to get rid of them (if a succeeding government wanted to abolish them). However that may also mean legislative changes for any major restructuring.

Flexible structure. If the Government is not sure how GBE will develop or whether its mandate will change over time, a private company limited by shares is going to be a lot more flexible, as any changes would be no more onerous that for a non-Government private company (assuming that the Government does not have a golden share).

Speed to market. Given the Labour party is making GBE a key part of their election pledges, there will be a lot of tasks around GBE that will need to move in parallel. GBE will only be able to start signing contracts and making decisions when it is incorporated. A private company limited by shares is going to be quicker, as final details can be ironed out during the incorporation process rather than having to be agreed in legislation.

Legacy. A smaller point but an incoming government might, all things being equal, want a legislative company to give the appearance of permanence.

From these points, and given (a) the complexity of GBE and (b) its ability to evolve over time, it seems sensible to prioritise speed and flexibility for GBE, so the Government may wish to look at the private limited company – with shares rather than limited by guarantee, for reasons discussed below.

Although messages are sometimes mixed, it is clear that GBE is going to be the foundation stone of Labour’s energy policy. It will develop green energy technology in the UK, accelerate the development of green projects and also build a portfolio of income generating projects within and outside the UK. On this basis, and as mentioned at the beginning, the Government may be a shareholder, a lender and/or a guarantor on that basis. A private company limited by shares will allow for maximum flexibility, for example, to issue separate classes of shares where dividends are linked to individual projects, or as a form of debt, with a fixed dividend, or a class of shares are redeemable, when that capital is no longer needed. This flexibility will give the most options in negotiations with energy partners, and a greater number of options for the future usually results in a better commercial deal.

This has not been discussed or raised yet, but a private company limited by shares also has the benefit that the GBE could then issue shares to a third party. If the Government is keen to develop quickly a portfolio of income-producing assets, GBE may agree to purchase a portfolio of minority stakes in existing green power assets in Europe, to be paid for by issuing shares in itself (so an asset swap). This has the advantage of speed, and that income could meet a Labour pledge that GBE will be cash neutral over the medium term. However, even with a flexible corporate structure, this is still a project that will need to be started immediately in order to have a tangible result (operational asset, income-producing portfolio) in the first term.

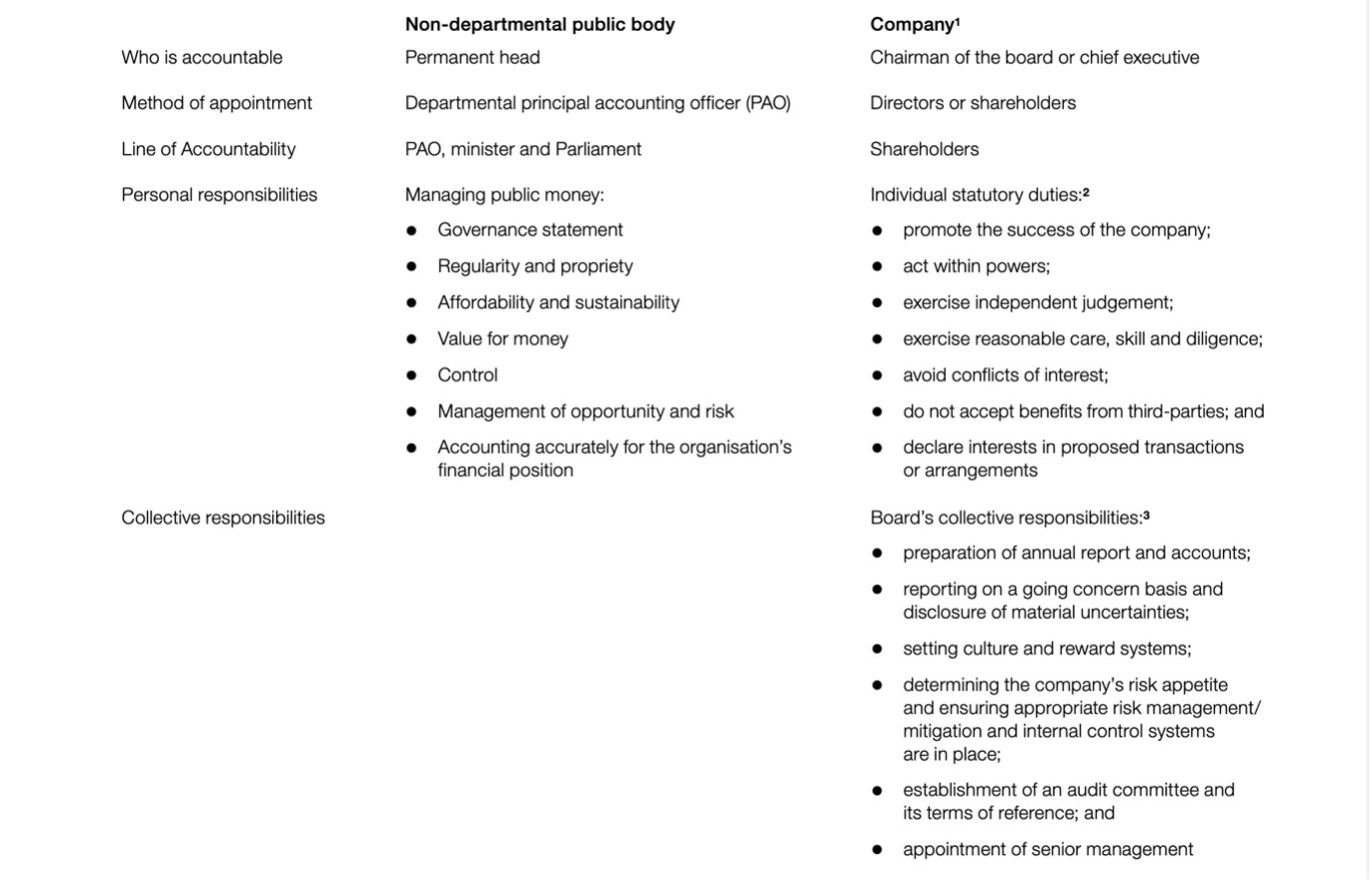

A Handy Guide

This graphic was useful (again from the 2015 National Audit Office report) showing some of the differences in governance and accountability.

Comparable Examples?

I have picked two examples where a private limited company structure has been used, one where the hard initial work has been put in and one which has a whiff of gimmick.

UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB)

This is a well thought out way of using a private company. The role of UKIB is to offer private sector financing and guarantees focussed on regional transformation, tackle climate change, delivering a positive financial return and using their investment to anchor significant private investment. This is a good example because some of that mission is what we would expect GBE to do. In fact, an option for GBE bearing in mind ‘speed to market’ would be to second the energy infrastructure team from UKIB to accelerate breaking the ground on UK green energy projects.

The relationship between UKIB and its Government owner is governed by a framework document that is clear and precise. It would be a very good idea for those establishing GBE to start with a document like this, which then leads the development of GBE and its business decisions. A formal document like this is an important part of the state management of a company like UKIB and GBE where the senior management team will be from the private sector, experienced in their sectors.

There is a publicly available strategic plan, and in all its dealings the UKIB show admirable transparency.

Great British Nuclear (GBN)

This is an interesting one. Although launched with a fanfare, it is in fact a trading name of the old British Nuclear Fuels Limited (BNFL), founded in 1971 and rebadged. There is little transparency – although there are press releases on the government website, showing some interesting tender activity, it does not have a website, so there is no way to see its mission, its relationship with the Government and its governance. Also, with no reports it is impossible to see if it is meeting its goals. In particular, it is not possible to see how it is leveraging in private finance (if that is indeed its mission) or how it is planning to generate a financial return. In short, it could be promising but my suggestion would be that GBN’s activities are logically wrapped into GBE with the same levels of governance and transparency as we have suggested.

Summary

There is much around GBE that still needs to be developed. As such, an incoming Government will need flexibility to finalise detail and move quickly when it does. Given the fluid nature of the energy market and the pace of green developments, GBE’s resilience will also lie in its ability to adapt. The Government may also want to be more creative, such as forming a partnership with another state-owned energy company like Equinor (Norwegian state energy company). A company limited by shares offers the biggest number of options for any such negotiations.

I am aware that we have not taken into account Treasury state aid or investment rules, relying instead on live examples of state-owned companies, but I hope that this gives some idea of how to start the GBE journey in the best and most resilient method.

*1- 'NAO ‘Companies in Government’ December 2015'

Cover: stock