Energy pricing in

the UK:

an election summary

Steve Wardlaw, June 2024

In case you had missed it, it’s election time. Given the focus in this election on energy security, this short article summarises how energy pricing works in the UK, its faults, and are we really dependent on the whims of Vladimir Putin…

A fuller piece will follow on the interaction between the two important markets, wholesale (how generators sell to suppliers) and retail (how suppliers sell to consumers) and how any upcoming government should insist on rapid reform.

The Energy Price Cap

This was created by OFGEM on 1 January 2019 to replace the discredited system of RPI-X, where the regulator simply set a price that it thought would be the price in a free market, and then did not concern itself with how much profit a supplier made as long as it met its obligations under its energy supply licence.

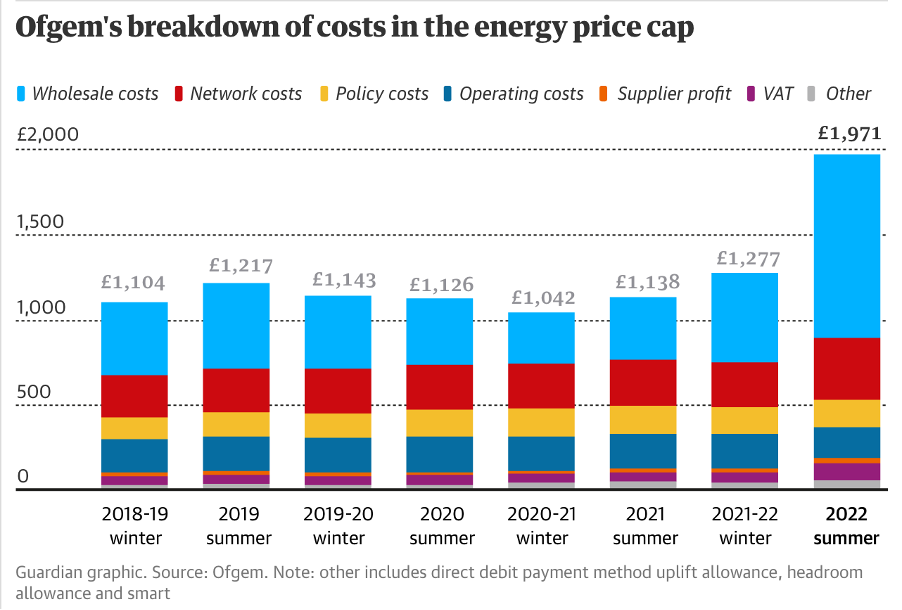

Here’s a breakdown of the energy price cap up to 2022:

So we can see that the issue for consumers is that there is a spike in wholesale costs (we will discuss wholesale pricing and why gas is still important further below). Some points to note:

This energy price cap is not an absolute cap. It is based on an average household. If you live in a larger than average property, then your bill will be higher. It is a per unit cap.

The energy price cap only applies to domestic retail customers and not businesses. This means that businesses take the full pass through of the recent wholesale price spike. So if you are wondering why your local bar or restaurant has closed down, uncapped energy costs could be the answer.

One can see from the chart that there has been a gradual increase in ‘network costs’ in red. These are costs of transmission incurred by the system operator in delivering power from generator to grid supply points. These have been forecast to rise as the national grid system fails to adapt to the new generation models. For example, there is significant wastage in transmitting power in the high voltage network (which then supplies the low voltage networks that consumers use) – fully 8% of power generated. So the system operator has to ‘constrain on’ (ask to run) other reserve generators and then charge those extra generating costs as system costs. Similarly, generators get constrained on where renewables are scheduled to run but cannot because of capacity constraints in the system. Again, this is something that needs to be fixed as the distribution of generation changes from north to south (in fossil fuel days) to east to west (in offshore wind days).

But the large section is blue – wholesale costs. And this shows the limitations (speaking politely) of the energy price cap. Apart from all the qualifications above, the wholesale price cap is not an absolute “pass through” ie where all costs are recouped. It is roughly based on an average acquisition price for power from all sources, such as long term contracts with generators (tending to be a lower price) and the spot market (tending to be a higher price)

What does this mean for suppliers? Well if you are an older established supplier you will have a portfolio of lower and higher priced assets, so an average price works. However, if you were one of the new energy suppliers (note the past tense), then you had no long term contracts with generators and bought your power on the spot market. Thus an average price simply does not cover your costs. As a result, in 2021 and 2022, 28 new energy companies collapsed.

A good regulatory system is designed to be resilient – so built to withstand market shocks (or is transparent about the effects of market shocks). OFGEM’s energy price cap did neither. Thus we have a situation of having a regulatory tool that (a) does not cap costs to consumers, (b) drives hospitality venues out of business and (c) in a stroke removes all the new entrants to the market that were supposed to encourage actual competition.

Reform is needed and this will be the subject of future papers. However, given the increasingly decarbonised generation profile in the UK, let’s have a quick look as to why global gas prices are still so important in the UK power market.

Wholesale Power Market Pricing

As mentioned above, there are several ways that suppliers can buy power from generators – through long term contracts, via a system of contracts for difference that the government has used to fund new green generation, and through the spot market (which is the market where suppliers and other major users can buy power in real time for supply the next day).

Of those three, the spot market is the most volatile, and the recent spot market price increases bankrupted nearly all the new suppliers, who were reliant on the spot market (not having had the capital balance sheet or longevity to be investing in long term generation contract) and who did not hedge.

In the spot power market, the price of gas effectively sets the price for power. How is this, given the varied generation mix?

This is because the spot/day ahead market uses a pricing mechanism called ‘system marginal pricing’. In this market, all generators who want to bid will bid the price at which they are willing to sell. These are then stacked in price order (merit order).

Renewables will tend to be cheaper, as will nuclear, because they do not use fossil fuels. Also nuclear is a ‘must run’ technology so will bid low to make sure that it is always in the mix.

Then the market operator will look at demand. Where those two lines of supply and demand cross, the price of that power determines the ‘system marginal price’ that is paid to all generators for that period. In practice, because gas fired power generation is flexible but expensive, the system marginal price is mostly set by a gas fired generator as there is insufficient flexible renewables over time.

Thus, all spot market power generation (40% of the total power purchase by suppliers) is set by the price of gas. And this price is based on the global price of gas – so any destabilising event, such as war in Ukraine, will reduce supply and increase nervousness, thus driving up the prices globally, which drives up the market price to buy gas for the UK, which drives up the price for gas generation, which drives up the price of 40% of the UK power market, irrespective of how that power was generated.

Phew. This is what the next government will need to deal with.

In the coming weeks I will go through options for reform of both the market and its pricing. This is just a very brief summary of how the pricing works in the pre-election period, where ‘energy security’ will be discussed, hopefully as more than just a buzzword.

June 2024.

Cover: stock